Plesiosauria

Plesiosaurs (=Plesiosauria) are a group of secondarily aquatic carnivorous reptiles belonging to the clade Sauropterygia within the diapsid clade Euryapsida (Taylor 1989, Caldwell 1997a). Plesiosauria has retained phylogenetic validity for about 190 years, since the formal identification of the group by de Blainville (1835). Unfortunately, this long history has hindered modern systematics of the group.

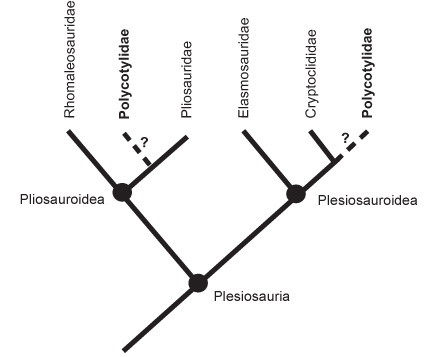

The order Plesiosauria consists of two superfamilies. The Pliosauroidea (often termed pliosaurs) are typically short-necked, whereas the Plesiosauroidea (often also termed plesiosaurs, but it gets complicated) are typically long-necked. However, generalisations based on neck length are now considered unreliable as research into plesiosaur evolution and phylogeny continues to reveal a more complicated story. The family Polycotylidae, for example, is a Late Cretaceous group of short-necked plesiosaurs that were traditionally regarded as pliosaurs. However, cranial ananomy (Carpenter 1997) points to a plesiosauroid affinity for them. Similarly, the pliosauroid genus Attenborosaurus is a pliosaur with a relatively long-neck.

Cladogram of Plesiosauria

The simplified cladogram above shows the main families within Plesiosauria and the alternative phylogenetic positions proposed for the Polycotylidae relative to the other main families. The general consensus today is that polycotylids (=Polycotylidae) are plesiosauroids (=Plesiosauroidea) and this is the classification I have adopted for this website.

Contrary to some popular accounts (e.g. Lambert et al. 2001; Smith 2003a), plesiosaurs were not an exclusively marine group and remains are now widely known from freshwater and lagoonal deposits (e.g Wiffen and Moisley 1986, Cruickshank 1997, Sato 2002). Ambiguous plesiosaur material occurs in Middle Triassic deposits (Benton 1993a) but the first diagnostic plesiosaurs are uppermost Triassic in age (Taylor and Cruickshank 1993b; Storrs 1994, Storrs 1997). The lineage reached a cosmopolitan distribution by the Early Jurassic, a maximum diversity in the Late Jurassic (Sullivan 1987) and persisted successfully to the Uppermost Cretaceous. Plesiosaur vertebrae of putative Palaeocene age were wrongly dated (Lucas and Reynolds 1993).

Plesiosaur characteristics

The Plesiosauria is characterised by a suite of derived characters and secondary adaptations to life in the water. All plesiosaurs have four large flippers and rigid broad bodies. They all possess the following synapomorphies (shared derived characters) in their skeleton (Rieppel 1997, Carroll 1988, Storrs 1993):

- Ventrally expanded (lengthened and plate-like) pectoral and pelvic girdles

- Nasals (nasal bones) absent

- No contact between ilium and pubis

- Relatively short trunk (body) and tail

- Well-developed gastralia (‘belly ribs’) forming a tight ‘basket’

- Hyperphalangy (increase in the number of bones in the digits)

- Short and broad ‘long bones’, in the limbs, particularly the propodials and epipodials, which have transformed the limbs into flippers, of which both fore and aft are similar in shape and size.

- Paired nutritive foramina subcentralia (small openings for blood vessels or nerves) on the vertebral centra (one exception is Brachauchenius, and in some other pliosaurs the foramina are reduced)

Within the lineage, pliosauromorph forms with large heads and short necks were more rapid and manoeuvrable swimmers than plesiosauromorphs with long necks and small heads Robinson 1975, Massare 1988, O’Keefe 2001b). Despite these general morphotypes, the gross morphology of the postcrania remained conservative throughout the evolution of the group (Carroll 1988, Storrs 1999). Famously described by many, including Owen (1860) “as a snake threaded through the trunk of a turtle” (p. 230). The typical plesiosauroid bauplan (body plan) was spectacular enough to defy the belief of scientists at the time (Taylor 1997, Cadbury 2000) when Mary Anning discovered the first complete Plesiosaurus in 1823. The name Plesiosaurus was coined two years prior for remains “presenting many peculiarities of general structure” (De la Beche and Conybeare 1821)(p.560).

Plesiosaurian clades

The chart below is a nested classification for Plesiosauria. Note that some classifications have placed Rhomaleosauridae outside of Pliosauroidea (=pliosaurs), but I have used a traditional approach and nested Rhomaleosauridae within Pliosauroidea.

Sauropterygian clades

The chart below is a nested classification for Sauropterygia to show the relative position of Plesiosauria.