Resurrecting the Unfortunate Dragon

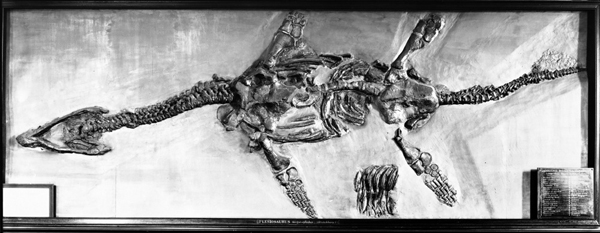

The five metre-long holotype specimen of ‘Plesiosaurus’ megacephalus, from the Jurassic of Street-on-the-Fosse, Somerset, was one of several plesiosaurs once displayed in the Bristol Museum and Art Gallery. As one of the earliest plesiosaurs to evolve it is an important species for understanding the early history of the group. Sadly, the fossil skeleton was destroyed along with many other important specimens when the museum was struck by a bomb during the Second World War. This destroyed fossil material is sometimes referred to today as the ‘ghost collection’.

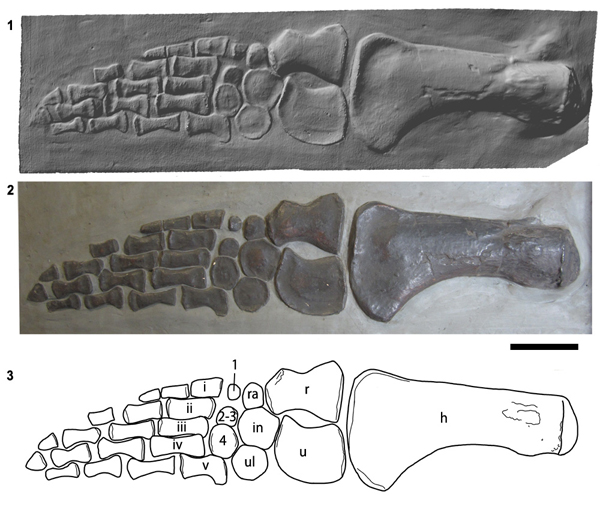

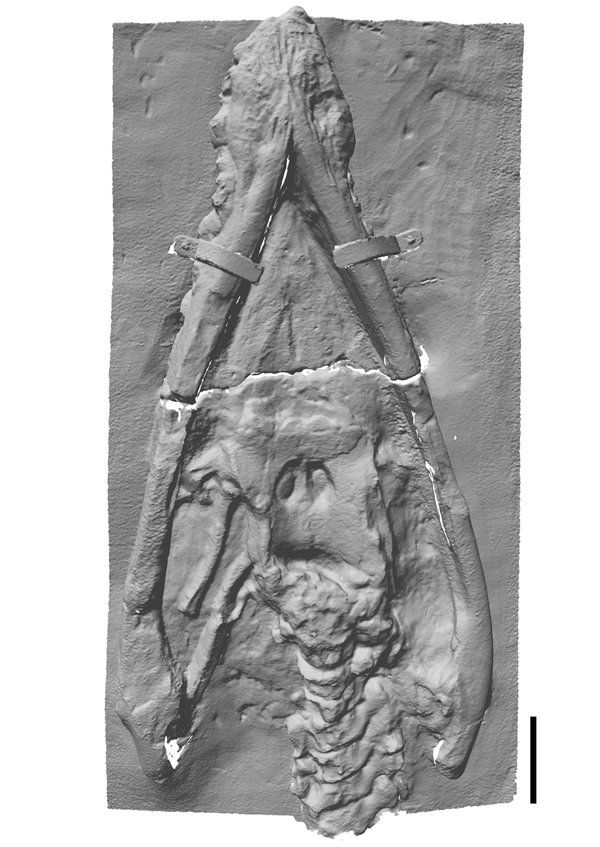

Thankfully, all was not lost. Moulds had been taken from some of the fossils before the war, and in the case of ‘Plesiosaurus’ megacephalus, multiple casts of its skull and forelimb were produced prior to its destruction. These were deposited in the collections of several museums, including the British Geological Survey (BGS), Keyworth; Natural History Museum, London; and Trinity College, Dublin.

The casts provide a valuable resource that I was able to use to describe ‘Plesiosaurus’ megacephalus in an article published this year in the open access journal Palaeontologia Electronica (18.1.20A p.1-19). The study focused on the casts held in the BGS, but was also facilitated by The Bristol Museum and Art Gallery who provided historical photographs of the ‘ghost collection’ from their archives. The photo (above), previously published by Swinton (1948), shows how the entire fossil skeleton appeared before it was destroyed. The BGS also produced three-dimensional digital laser scans of the casts as part of their JISC-funded ‘GB3D fossil types online’ project. The resulting virtual models are free to view or download (here) and can be rotated on screen or 3D-printed.

The skeleton of ‘Plesiosaurus’ megacephalus is distinct enough from all other plesiosaurs, including Rhomaleosaurus and Eurycleidus, to warrant a new genus name. I called it Atychodracon, meaning ’Unfortunate Dragon’, in reference to the unfortunate destruction of the original fossil material. This project also demonstrates that casts of fossils, and 3D laser scans, can provide valuable data for palaeontologists – they can be described, measured, and coded into analyses. When original fossil material has been lost, damaged or destroyed, the scientific value of casts increases even further. This study is the first publication to make use of the publicly available repository of 3D laser scans provided by the BGS. The Bristol Museum and Art Gallery is now investigating the possibility of using physical representations of their ‘ghost collection’ in future exhibitions, to bring long lost fossils such as Atychodracon ‘back to life’.

Find out more by checking out the article at Palaeontologia Electronica.