Polycotylus

P. latipinnis

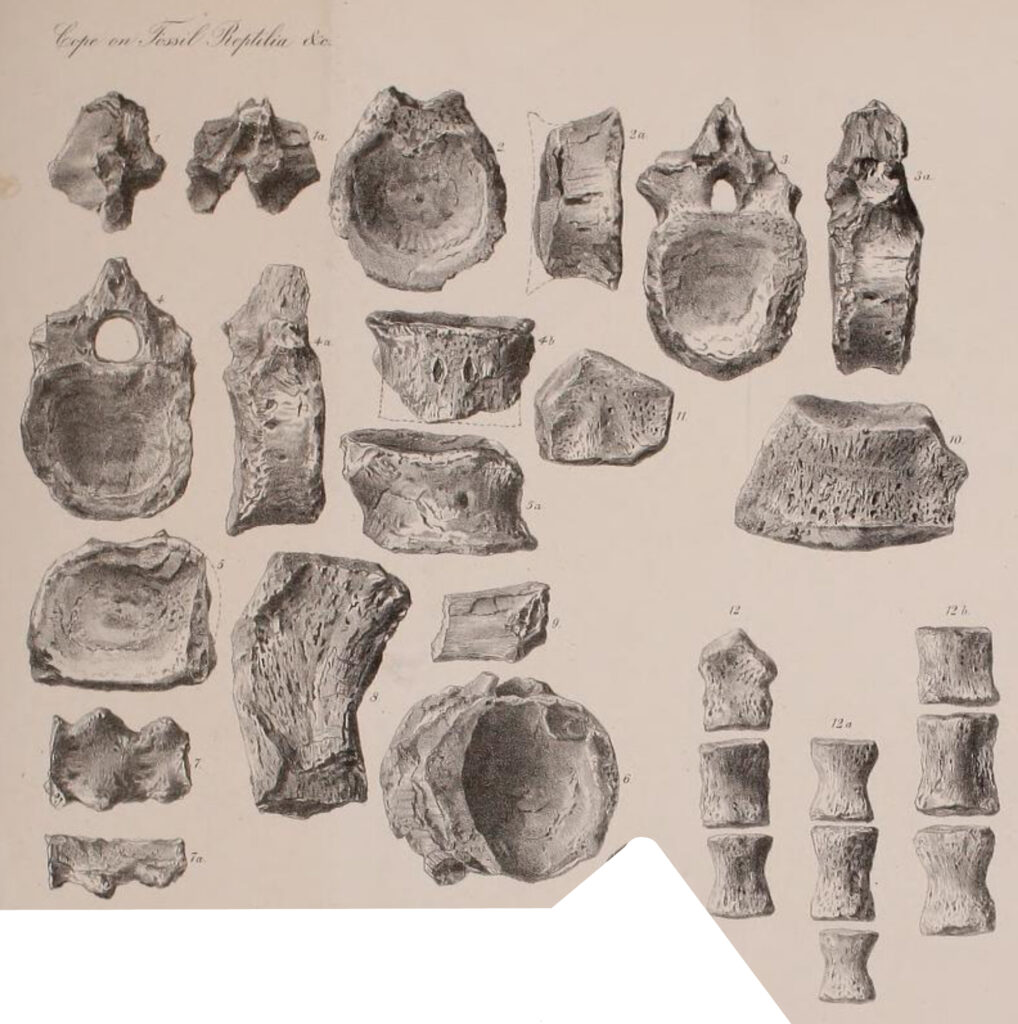

Polycotylus latipinnis was the first short-necked plesiosaur to be recognised in North America (Carpenter 1996), and the first polycotylid to be described and named (Cope 1869). It was established in the same volume that coined the name Elasmosaurus and contained the infamous ‘head on the wrong end’ reconstruction (Cope 1869). However, despite their equally long history, Polycotylus never achieved the same amount of fame as its long-necked cousin.

Cope only briefly described Polycotylus based on a rather scrappy partial skeleton, which was subsequently dispersed between two museums. This means the separate parts of holotype have separate specimen numbers (USNM 27678 and AMNH 1735) (Carpenter 1996).

Following Cope, Williston (Williston and Farrington 1903, Williston 1906) was the next person to reassess Polycotylus. He prefaced his notes in 1906 by explaining that “Polycotylus, described by Cope…from a number of mutilated vertebrae and fragments of podial bones, has remained hitherto much of a problem, and its characters have been very generally misunderstood”. Williston (1906) focussed his reassessment on, and figured the bones of, a different specimen to Cope (YPM 1125). Carpenter (1996) formalised this specimen as the paratype.

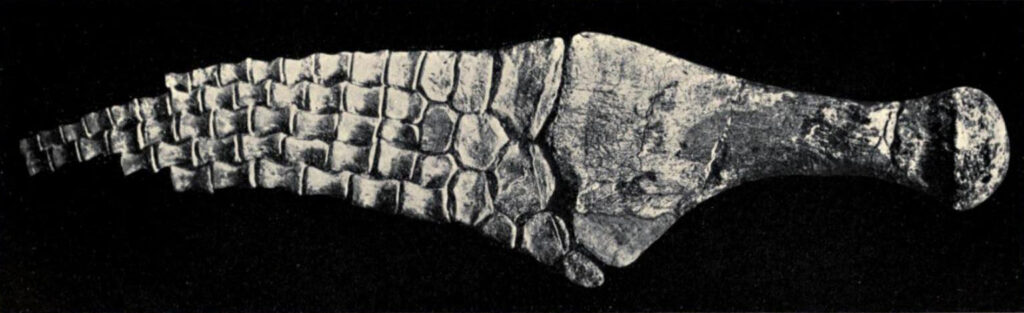

Williston and Farrington (1903) described and figured another rather fine limb, which they referred to Polycotylus latipinnis. They did not provide a specimen number or institution, but Storrs (1999) identified this specimen as KUVP 5916. The specimen is not listed as referred material of P. latipinnis in more recent assessments of Polycotylus (Schumacher and Martin 2015).

Williston (1906) also established another species of Polycotylus, P. dolichopus, for which he described two specimens, a hind limb (YPM 1642, which he also figured) and forelimb (YPM 1646, the holotype, which he didn’t figure). However, this species was subsumed into P. latipinnis (Storrs 1999), although it is not listed as referred material in the most recent assessments of Polycotylus (Schumacher and Martin 2015).

Williston and Farrington (1903) also erected the provisional new species Polycotylus ischiadicus, based on a partial skeleton including the pelvic girdle, but qualified this by saying “there is no assurance whatever…that they belong in this genus”. So, one wonders why he referred it to Polycotylus at all, and predictably, the specimen was shortly recognised as an elasmosaurid (Williston 1906). The species has its own complicated history (Storrs 1999). It was made the holotype of the elasmosaurid Thalassiosaurus by Welles (1943), before eventually being synonymised with Styxosaurus (Carpenter 1999).

A substantially complete referred specimen of Polycotylus latipinnis (FMNH PR 187 + 1629), found in 1949 in the Mooreville Chalk Formation of Alabama, was described by O’Keefe (2004a).

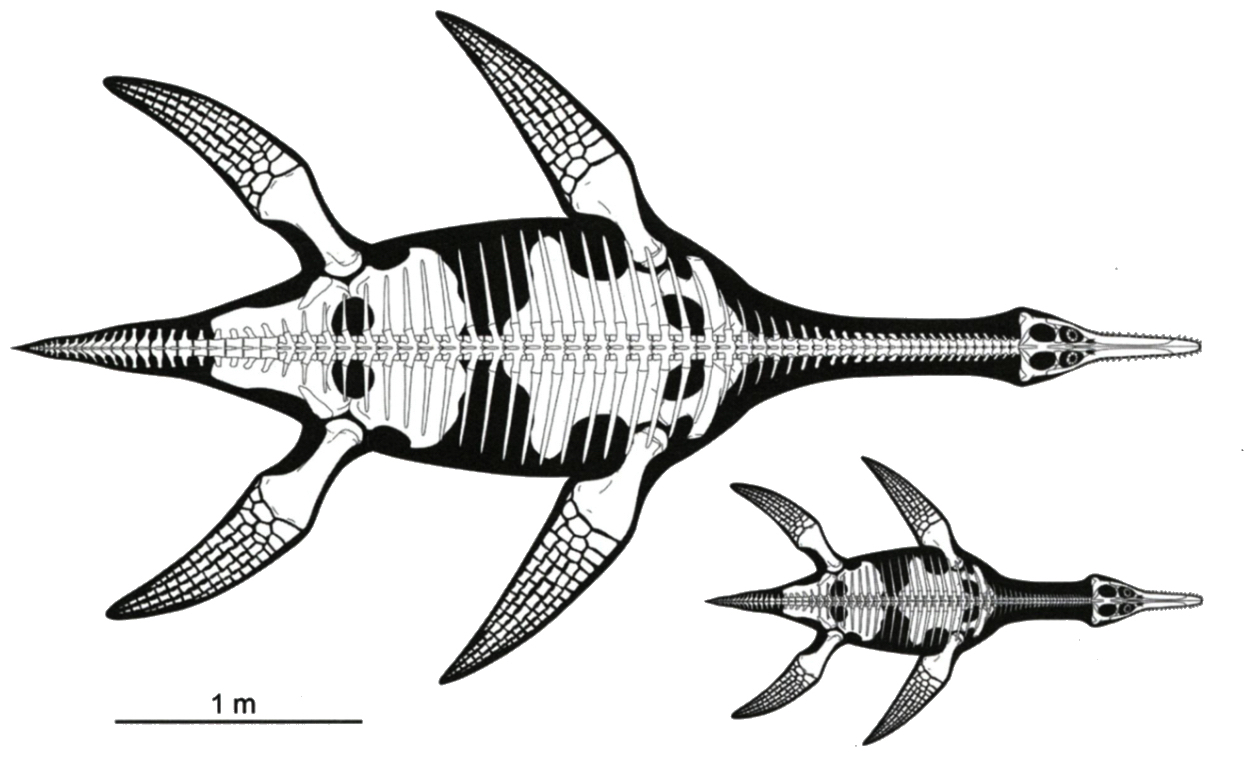

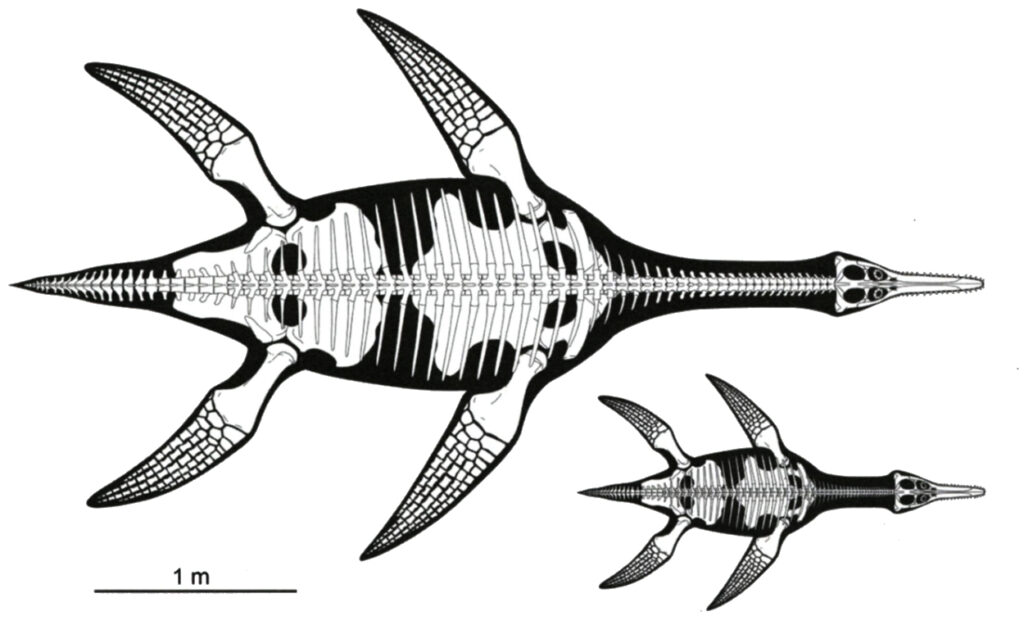

One of the most important specimens of Polycotylus latipinnis (LACM 129639) is also one of the most important plesiosaur specimens in general, because it provides the only known direct evidence for live birth in plesiosaurs (O’Keefe and Chiappe 2011). The fossil of the mother Polycotylus plesiosaur is preserved in with an embryonic fetus in its abdominal region.

A new species of Polycotylus was named by Efimov et al. (2016) for a substantially complete specimen in the Orsk Geological and Mineralogical Museum (OSMM 247) (Not the Undory Paleontological Museum as mistakenly stated by Efimov et al. 2016), from the Orenburg Region, Gaiskii District, Ural Mountains, Russia: Polycotylus sopozkoi. It is similar to P. latipinnis but presents some differences in the cranial and limb bones (Efimov et al. 2016, Zverkov et al. 2024). The specimen was redescribed and refigured by Zverkov et al. (2024) who corrected several erroneous bone identifications made by Efimov et al. (2016). The presence of Polycotylus in Russia demonstrates that it had a wide distribution across the Northern Hemisphere (Zverkov et al. 2024).

The name Polycotylus stems from the Greek ‘polys’ meaning much or many, and the Greek ‘kotyle’ meaning hollow or cup, so it translates as “very cupped”. This is a reference to the deeply cupped articular surfaces of its vertebrae.

Polycotylus is one of the largest polycotylids, with adults approaching 5 metres long. Schumacher and Martin (2015) provided the most recent technical diagnosis for Polycotylus latipinnis: “Posterior pterygoid plate extends beyond occipital condyle, posterior edge of pterygoid plates with coarse and irregular striate fabric; parasphenoid long and slender (ratio of length/width = 14), prominent anterior parasphenoid ossification (cultriform) projects into anterior interpterygoid vacuity; short temporal fenestrae, short and prominent sagittal crest; frontals elongate and extend well anterior of external nares; angulars and splenials extend anterior to midpoint of symphysis; robust teeth with subtle carinae, striae most prominent on lingual face; 26 cervical vertebrae; vertebral centra amphicoelous and short, anterior dorsals length/width ratio <0.55, dorsals with compressed walls; chevron facets shared on adjacent caudals, prominent on both posterior and anterior rims of centra, facets remarkably large and deep; ischia elongate; ilia strongly recurved and laterally compressed, articulation for ischium strongly medially inclined, sacral end reduced to knife-like tip with discrete sacral rib facets; propodials remarkably expanded posterodistally (length/width ratio for humerus »1.65), with minimally four distinct facets for epipodials, fifth epipodial may be present; metapodials exceptionally short, phalanges subquadrate, phalangeal count of digit III around 20. Other postcranial characters that may prove useful include scapulae with expanded ventral ramus and straight dorsal process, and pubes emarginated on the anterolateral border.”(p3).