Atychodracon

Sauropterygia

Eosauropterygia

Eusauropterygia

Pistosauria

Plesiosauria

Plesiosauroidea

Rhomaleosauridae

A. megacephalus

The genus Atychodracon was erected by Smith (2015) to accommodate ‘Rhomaleosaurus’ megacephalus, because it is generically separarate from Rhomaleosaurus sensu stricto (Smith and Dyke 2008). A. megacephalus is closely related to Eurycleidus and some authors have regarded A. megacephalus as a distinct species of Eurycleidus.

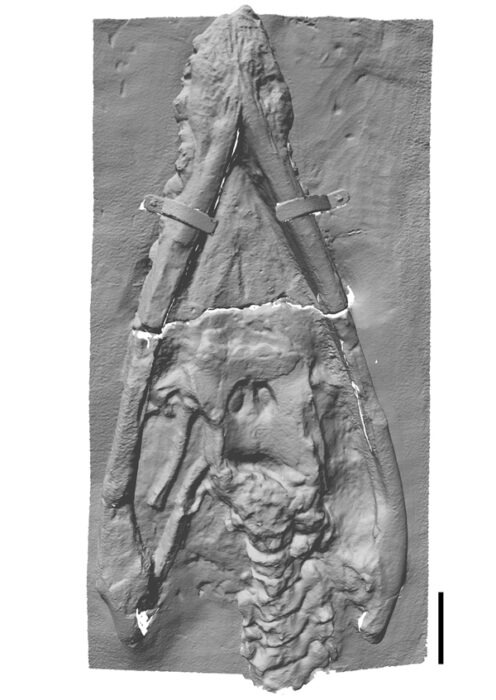

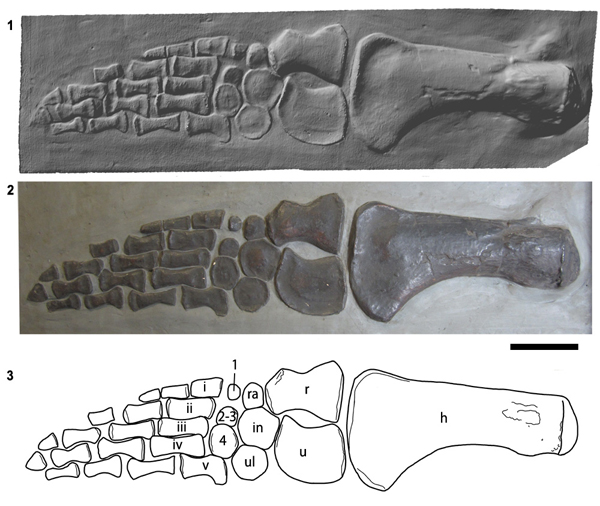

The holotype specimen of A. megacephalus (BRSMG Cb 2335) was a complete skeleton exposed in ventral view, housed in the Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery, but was destroyed by enemy action during the World War II Blitz. However, surviving plaster casts of the holotype skull and forelimb provide enough data for a modern diagnosis of the taxon. Casts are housed in the Natural History Museum, London (NHMUK R1309/1310); the Geology Museum, Trinity College Dublin (TCD.47762a, TCD.47762b; Wyse Jackson 2004) and in the British Geological Survey, Keyworth, Nottingham (BGS GSM 118410).

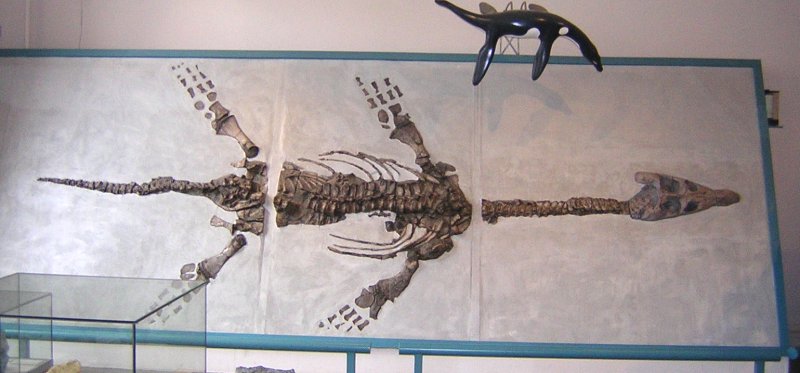

A neotype specimen of A. megacephalus was erected by Cruikshank (1994b). This fossil, nicknamed the ‘Barrow Kipper’ after the location it was discovered (Taylor and Martin 1990), is on display at the New Walk Museum in Leicester, UK. This specimen has become a referred specimen (Smith 2015). The skull of the Barrow Kipper was described in detail by Cruikshank (1994b) and is also on display at the New Walk Museum in Leicester, UK, in a case adjacent to the displayed skeleton. The skeleton has a replica skull cast from the original.

Cruickshank et al. (1991) proposed a specialised olfaction (or ‘underwater smelling’) system for plesiosaurs based on observations of the skull of A. megacephalus. The internal nares (or bony nostrils) on the palate are positioned anteriorly on the skull, and positioned anterior to the external nares on the dorsal skull roof. The internal nares are also associated with grooves that have been interpreted as an adaptation for channelling water into the nostrils. Under this hypothesis, the flow of water over the external nares was helped by the animal swimming, which maintained hydrodynamic pressure. The flow of water through the nasal ducts could have been ‘tasted’ by olfactory epithelia. If such a system existed it might have been a common adaptation among plesiosaurians, since all plesiosaurs have anteriorly positioned internal nares (Brown and Cruickshank 1994).

See my blog article from 2015 about my paper naming and describing the surviving casts of the holotype of Atychodracon.